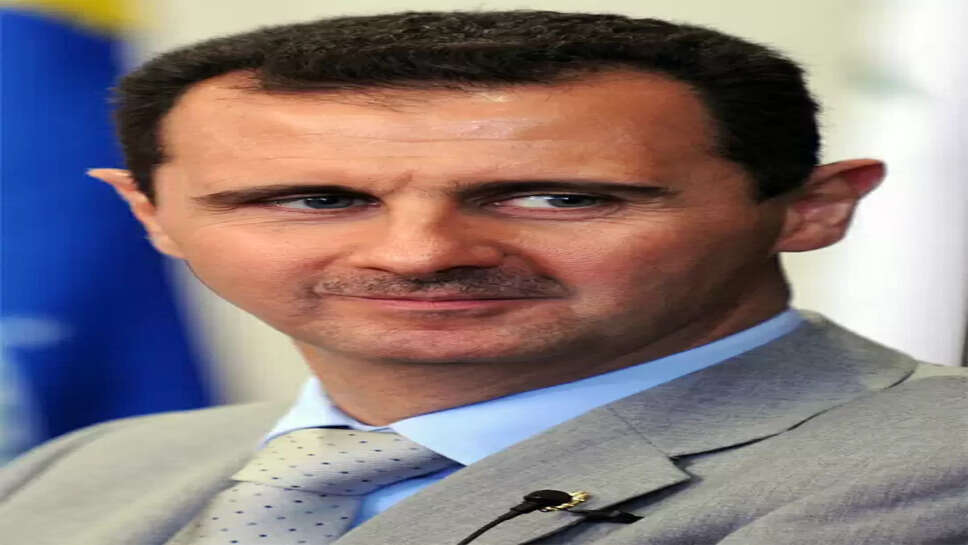

Syria’s Bashar al-Assad Faces Possible Trial in France for Chemical Weapons Use

A French court is set to make a historic decision that could reshape international legal precedent — whether Syrian President Bashar al-Assad can be stripped of his presidential immunity and tried for crimes against humanity, specifically for alleged chemical attacks on Syrian civilians. The move follows years of legal efforts by human rights groups, Syrian survivors, and international justice advocates seeking accountability for atrocities committed during Syria’s brutal civil war.

If the French judiciary rules in favor of lifting Assad’s immunity, it could open the door for a formal criminal trial against a sitting head of state — a rare, if not unprecedented, development in modern legal history.

The Charges: Chemical Attacks on Civilians

The case centers on two chemical attacks carried out in the city of Douma and the district of Eastern Ghouta near Damascus in August 2013. These attacks, which involved the use of sarin gas and other banned chemical agents, resulted in the deaths of more than 1,000 civilians, including hundreds of children. Videos and photographs from the attacks shocked the global conscience, showing lifeless bodies, foam around mouths, and victims gasping for air — classic symptoms of nerve agent exposure.

International investigators, including UN-backed inspection teams and independent NGOs, have documented the attacks extensively, often attributing responsibility to the Syrian regime. While the Assad government has consistently denied using chemical weapons and claimed the footage was staged, mounting forensic and testimonial evidence has painted a grim and damning picture.

The Legal Grounds in France

France is pursuing this case under its doctrine of universal jurisdiction, a legal principle that allows a national court to prosecute individuals for the most serious crimes — such as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes — regardless of where they occurred or the nationality of the victims or perpetrators.

French prosecutors argue that the use of chemical weapons, particularly against civilians, constitutes a clear violation of international humanitarian law. Moreover, they contend that such crimes are so severe that traditional protections like presidential immunity should not apply.

The court must now decide whether Assad, as a sitting head of state, can be considered personally responsible for these acts, and whether his immunity under international law can be waived in the context of crimes against humanity.

The Role of Survivors and Human Rights Groups

This case would not have been possible without the tireless efforts of Syrian survivors now residing in France and across Europe. Many of them have provided eyewitness testimony, video evidence, and medical records that link the attacks directly to Syrian government operations.

Human rights groups such as the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) have played a central role in gathering evidence and presenting the case to the French judiciary. These organizations argue that holding Assad accountable in a European court could set a powerful precedent for international justice.

“Our goal is not vengeance, but justice,” said one Syrian activist involved in the case. “We want the world to acknowledge the suffering of our people and make sure such crimes are never repeated.”

What Presidential Immunity Means — and Doesn’t

Under traditional international law, heads of state enjoy immunity from prosecution in foreign courts. This principle, designed to protect diplomatic relations and national sovereignty, has often shielded leaders from accountability, even in the face of well-documented atrocities.

However, the concept is increasingly being challenged in the post-Nuremberg era, where international law prioritizes individual responsibility for crimes like genocide and mass murder over state protections.

Notably, former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir was indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) while still in power, though enforcement of that warrant has been inconsistent. The case against Assad could build on this evolving trend, especially as the chemical attacks in question fall under banned warfare methods under the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, to which Syria is a party.

Political and Diplomatic Implications

Should the French court move forward with a case against Assad, it will inevitably create diplomatic ripples. Syria has already denounced previous attempts at foreign prosecution as “neo-colonial interference” and claimed that the accusations are politically motivated.

Russia and Iran, two of Assad’s staunchest allies, may view the French proceedings as an attack on Syrian sovereignty and an attempt to delegitimize Assad’s government. Moscow, in particular, has used its veto power at the United Nations Security Council multiple times to block resolutions targeting Syria for war crimes.

However, many Western governments and human rights bodies are likely to welcome the move as a bold step in the global fight against impunity. France, which has long advocated for international accountability mechanisms, could position itself as a leader in transnational justice.

A Long Road Ahead

Even if the court rules to lift Assad’s immunity, a trial is far from guaranteed. Assad remains firmly in power in Syria, and there is virtually no chance he would voluntarily appear in a French courtroom. France has no extradition treaty with Syria, and any attempt to apprehend him would rely on broader international cooperation, which is unlikely given current geopolitical realities.

Still, legal experts argue that such a ruling would be symbolically and legally significant. It would mark Assad as a wanted man under international law and potentially limit his ability to travel safely abroad. It would also put pressure on other countries to take similar legal steps, creating a network of accountability.

Moreover, a trial in absentia — while controversial — is not without precedent in European courts, especially in cases involving war crimes and terrorism. Legal scholars believe that even symbolic justice, when built on strong evidence, can serve a vital purpose.

Voices of the Victims

For many Syrian survivors, especially those who lost family members in the chemical attacks, the court case is not just a legal milestone but an emotional one. Some have expressed cautious optimism, seeing the French proceedings as the first glimmer of justice after years of impunity.

“We buried children with our own hands,” said a survivor from Douma. “The world moved on, but we are still stuck in that moment. If this court listens to our stories, it means the world hasn’t forgotten us.”

A Test for Global Justice

The French court’s impending decision on whether Assad can be tried for war crimes will be closely watched around the globe. At its core, the case raises difficult but vital questions: Can a sitting head of state ever be truly above the law? Do international principles of justice apply equally to all nations? And can survivors of atrocities ever hope for accountability?

Regardless of the outcome, the proceedings represent a courageous legal challenge to the notion of untouchable power — a rare act of defiance against the normalizing of wartime atrocities. As the world continues to grapple with authoritarianism, conflict, and humanitarian crises, the verdict in this case could redefine the boundaries of international justice for years to come.